Just like me in general, my blogging has become awfully slow recently! With only two months, almost to the day, to go until our little wriggly baby arrives I am feeling somewhat cumbersome these days and everything is taking me a bit longer than it used to!

Even though I’m not making very much at home, I’m still going to college so I thought I’d share with you where I’ve got to with my 1940s dress.

Having found a squillion patterns that I love at The Vintage Pattern Store, I managed to narrow the choice down to this one.

Originally I was going to use the existing pattern to make a toile and then a final dress, but a couple of factors changed my approach:

1) The point of a toile is to check for fit before making the real garment. However, when you look like this, it is unlikely that many things are going to fit you no matter how many toiles you do…

2) Pattern cutting is the element of all the courses that I do that I enjoy the most, and want to learn the most about. So just using an existing pattern won’t help me develop those skills very much.

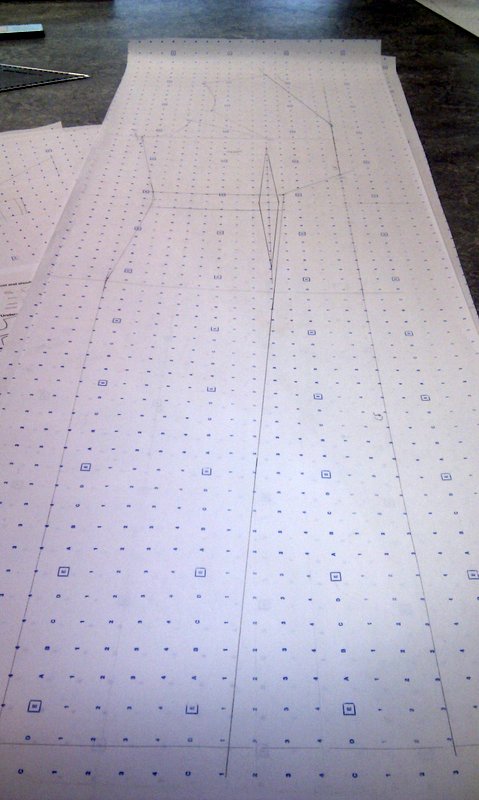

SO, instead I am creating the dress pattern from scratch using the image above as reference. I have my pre-pregnancy measurements so am using them in the hope that one day I may shrink back to normal size! I can then compare my pattern with the original at the end to see how we approached things differently. I’ll also make a toile once I’ve done the pattern, but won’t be able to fit it for a while!

So far I’ve used the same bodice block as I did for my 1930s dress, and created a basic dress block. It is then from these that you make adjustments to create the different elements of the dress – that’s the fun bit!

This is the front of the dress, with all the different bits still in one piece. The next stage is to isolate each section (eg skirt, or bodice), and then make any adjustments needed.

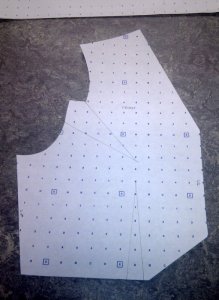

This is the bodice pattern piece.

I then moved the bust dart to the shoulder to allow me to create the pleats on the shoulder of the dress.

There are a few stages in between, but in the photo below I have added the shoulder pleats to the pattern, and opened out the bottom of the bodice to create the gathers at the front of the dress where it meets the waist.

See, I look just like the model in the illustration!